Dr Tom Jenkins, Musculoskeletal GP with Expertise in Sport & Exercise Medicine

With Wimbledon season approaching, many people begin to think about tennis—and ironically, so do many of my patients, though not because they’re picking up a racquet. Instead, I see a spike in consultations for “tennis elbow”, or more accurately, lateral elbow tendinopathy. The funny thing is, very few of these patients play tennis.

In fact, I tend to think of it as “Office Elbow”. In clinic, the most frequent culprits are people who use a keyboard and mouse extensively. The condition often results not from explosive strain, but from sustained or repetitive wrist use—for example, hovering a hand over a mouse for long periods, or repeatedly lifting the hands up onto a keyboard. The cumulative load placed on the wrist and finger extensor tendons eventually takes its toll.

The Anatomy Behind the Pain

The muscles that extend your wrist and fingers—particularly the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB)—share a common attachment at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, known as the common extensor origin.

This area becomes overloaded through repeated wrist extension or gripping tasks, especially in awkward positions. Over time, the tendon begins to show degenerative changes, rather than inflammation—hence why “tendinopathy” is now the preferred term over “epicondylitis.”

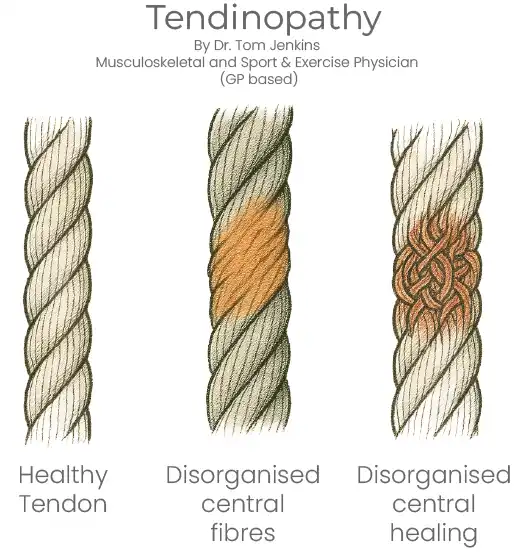

The Fraying Rope Analogy: What Happens in Tendinopathy

One helpful way to understand tendinopathy is to imagine a healthy tendon as a strong, wound rope. In tendinopathy, the inner fibres begin to fray—not from a single tear, but from repeated micro-damage. If left untreated, these frayed fibres heal in a disorganised and chaotic fashion—like tying together hundreds of tiny fragments, forming a tangled ball of elastic bands within the rope.

This leads to:

- Swelling or thickening

- Pain with loading

- Stiffness or weakness

- Loss of grip or function

Physical therapy acts like a guide, helping those disorganised fibres realign properly. The goal isn’t just to relieve pain—it’s to restore structure and load tolerance so the tendon can function again.

When to Consider Imaging

In most cases, diagnosis is clinical. But Ultrasound or MRI may be used, particularly when:

- Symptoms have come on suddenly, raising concern about a partial tendon tear

- There is severe loss of strength

- The condition is not responding to conservative treatment

Imaging helps rule out tears, confirm the diagnosis, and assess the degree of tendon degeneration, which can provide helpful information about prognosis and likely recovery time.

What Happens If It’s Left Untreated?

Without structured treatment, symptoms may persist for months or even years. As tendon quality deteriorates, pain can become constant, affecting daily tasks like lifting a kettle or turning a doorknob. The tendon becomes more sensitive, and strength can reduce dramatically.

Aims of Treatment and Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation aims to:

- Remodel the disorganised tendon fibres

- Restore strength and load tolerance

- Prevent chaotic scar tissue and encourage proper fibre alignment

In my clinical experience, the duration of symptoms often predicts the duration of recovery. For instance, someone with a six-month history of symptoms will typically need a similar timeframe of progressive rehab to achieve full resolution.

Treatment Options – From Least to Most Invasive

1. Ergonomic Adjustments

Simple changes—such as improving desk setup or switching to a vertical mouse—can significantly reduce strain on the extensor tendons.

2. Exercise-Based Physiotherapy

Guided loading (especially eccentric and isometric exercises) helps realign collagen fibres and restore function.

3. Bracing / Counterforce Straps

May reduce strain temporarily, useful for pain relief during activities but not a cure in isolation.

4. Shockwave Therapy

A non-invasive option that can stimulate healing in chronic cases, though outcomes vary.

5. Injection Therapy

- Corticosteroid injections may offer short-term relief, but current guidance discourages their routine use for lateral epicondylitis due to high recurrence rates and worse long-term outcomes (Versus Arthritis, NICE).

- Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) is gaining interest for chronic tendinopathies. Evidence is evolving, but PRP may support tendon healing by delivering growth factors directly to the site. It’s not widely available on the NHS.

Injections can change the speed of recovery, but only rehabilitation changes the direction. A good injection must be embedded in a well-structured rehab programme—without this, there’s a risk of temporary relief but no long-term progress.

6. Surgery

Reserved for severe or refractory cases, usually after 6–12 months of failed conservative care.

Final Thoughts

Tennis elbow isn’t just for tennis players. It’s a load-related tendon condition, often seen in desk workers and manual labourers alike. With the right diagnosis and rehab strategy, it’s highly treatable—but early intervention is key.

If you’re struggling with persistent elbow pain, a comprehensive assessment and tailored rehab plan can help you get back to doing what you love—whether that’s tennis, typing, or lifting your morning coffee pain-free.